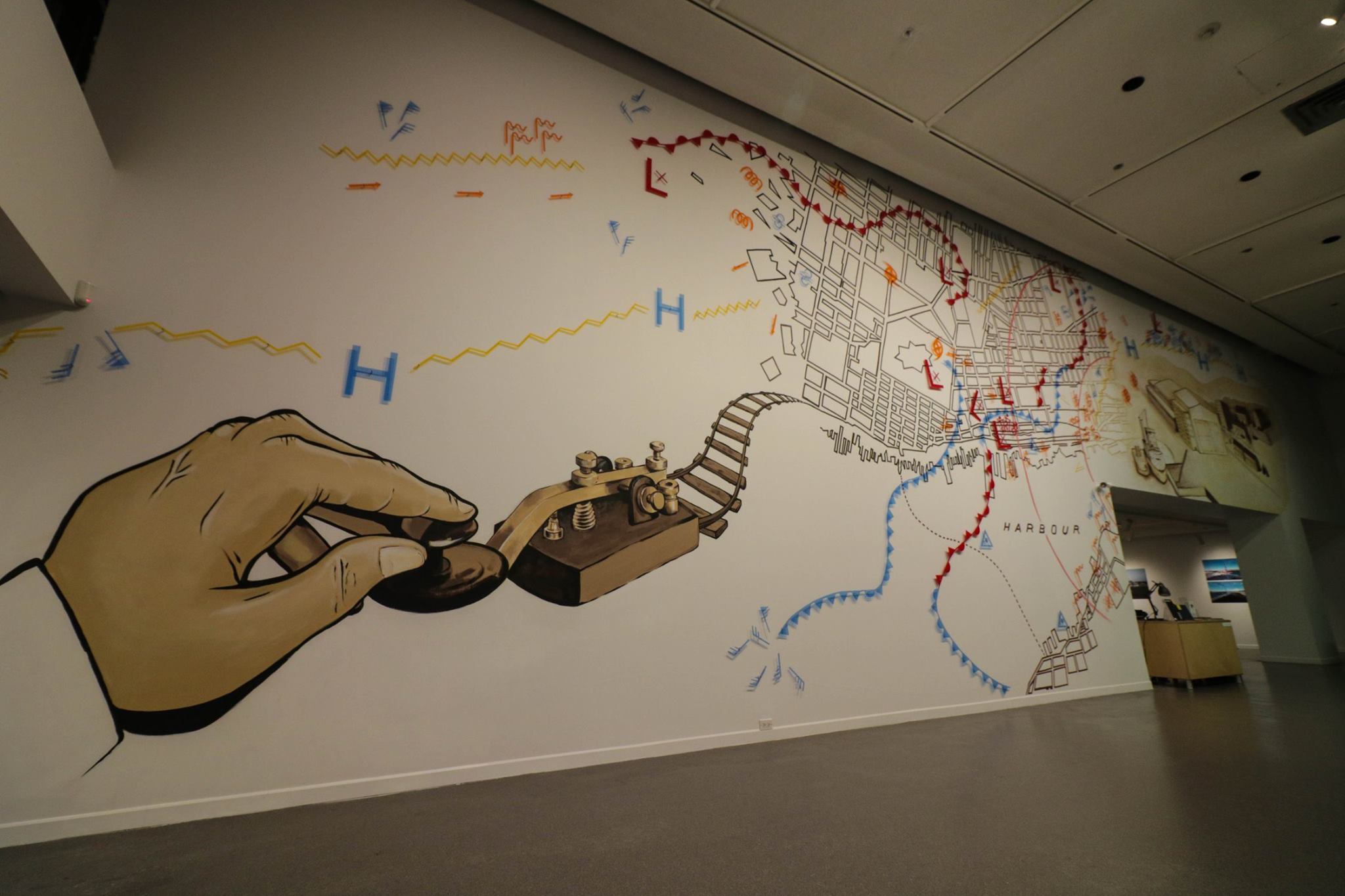

At approximately 8:45am on December 6, 1917, the SS Imo and the SS Mont-Blanc collided in the Narrows of the Halifax harbour. The resulting sparks ignited a heavy load of munitions on the Mont-Blanc that was intended for the battlefields of WW1. As the relief vessel Imo drifted towards Dartmouth, the crew of the Mont-Blanc abandoned their blazing ship and rowed their lifeboats across the harbour towards safety, reaching shore at the Mi’kmaq settlement of Turtle Grove. Wedged alongside the wharf at Pier 6 on the Halifax waterfront at the foot of the working class neighbourhood of Richmond, the Mont-Blanc exploded at 9:04:35. No one other than the Mont- Blanc crew and the harbour pilot had been notified that the ship was loaded with a lethal cargo of munitions. The resulting explosion, tsunami and fires that raged through the neighborhood of Richmond killed almost 2000 people and injured 9000 more. Thousands of homes and businesses were destroyed. The Halifax Explosion was the largest human-made explosion until nuclear weapons were used to annihilate Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

NiS+TS’s work in the debris field of the Halifax Explosion demonstrates how the past and present haunt the future, and asks what is learned through a contemporary practice of exploring interdisciplinary methods for creating historical knowledge and understanding. The Halifax Explosion was not an accident. It was an inevitable and predictable wartime disaster that was inflicted on a civilian population that was far from the battlefields. Like most disasters, it affected indigenous people, the working class and poor disproportionately. The work of providing relief, support and solidarity, and then of rebuilding the city, was carried out primarily by those same communities of everyday people. In the ongoing militarization of the cultural landscape of the harbour, the burden of impending disaster continues to be borne by ordinary people.

Disaster, along with moments of social upheaval, is when the shackles of conventional belief and role fall away and the possibilities open up. –Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster (New York: Viking, 2009) 97